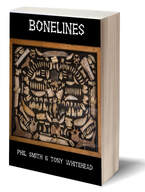

BONELINES

Phil Smith & Tony Whitehead

|

In Guidebook for an Armchair Pilgrimage, authors Phil Smith, Tony Whitehead and photographer John Schott lead us on a ‘virtual’ journey to explore difference and change on their way to an unknown destination. They create a pilgrimage we can all follow, even if confined to our homes.

In researching the Guidebook the authors went on an actual journey. Bonelines is the secret story of that journey. Given the present circumstances it now appears prophetic, prescient and helpful, so we have decided to bring it into the light. It is written in novel form and will be published online in weekly instalments. Here is the first instalment. (You can find details - and order a copy of - Guidebook for an Armchair Pilgrimage here.) |

Bonelines

Instalment 11 (Chapters 61-67)

Tony Whitehead & Phil Smith

Chapter 61

“Who are you? How are you going to save us? Are you something to do with the three statues in the graveyard?”

“Don’t try to explain us,” growled Mary.

The angels seemed more human, faced by swelling hordes of Hexameron allies. Even as the four gazed over the fields from the gardens of Mandun Hall, the widespread forces thickened. What Mandi had imagined were shadows thrown among the fox-hounds by the hunt’s rides were also dogs, dogs the size of horses with black coats and blood-red eyes. Some of the lights that she had thought were dull glare from employees’ screens, she could see now were the depredated bodies of those the white snipers had lured over the cliff tops; their broken limbs and blanched skins drunkenly lolling. The white-coated programmers, re-grouping now from the ruins of Mandun Hall and ill at ease with their improvised weapons, were no less unreal.

“You’re the saints, then? In my dream, in the paintings in the church...”

“Stop trying to rationalise,” Apollonia upbraided her. “Those paintings are real enough...”

“Maybe she lined up on the wrong side?” spat Sidwella, cuttingly.

“This is what is,” said Mary, and her wings fluttered over the ranks of the Hexameron forces. “There are no explanations.”

The Chairman of the Hexamerons broke ranks and stepped into the empty ground between the two sides. A hush rippled back along the Hexameron troops, down the vale, up the hills and to the horizon.

“Amanda!” He pressed the palms of his hands together, as though he were about to pray; but suddenly held them up, to either side of his head in a gesture that might have been surrender or receiving adulation. “Nothing escapes death. That is the one great truth. But sometimes we Hexamerons like to give things a nudge...”

“Mandi?

“Mandi? Is that you?”

“O my... Mandi, Mandi!”

“It’s us!”

A rumpus in the ranks of the white-coated programmers, beyond a riot of Wisteria still clinging to the corner of the property, resolved itself into two parts, and between them Anne and Bryan were running towards Mandi and the angels. The same Anne and Bryan; the Anne and Bryan with the irritating invisible make-up and the over-brazen bald patch and untidy jacket.

The chairman held his left palm towards them and brought them to a halt.

“Please,” begged Mandi’s mother. “Our little girl!”

“In a moment! You would have waited hopelessly for a lifetime without us!” The chairman turned back to Mandi. “Did you think we had killed your mother and father in order to bring you here and make all this happen? Or did you suspect your precious angels were behind it? You were always so sceptical of conspiracy theories...”

“You’re fucking with my head!”

“Tut tut, my dear. Not in front of ‘mother and father’. You think you are so important? The programmes produce such illusions for millions everyday! Do you think you’re the only one who dreams of having better parents? Or just having any parents at all? Send your friends,” and he nodded cautiously at the angels, “back to whatever chaos they came from.”

“I wouldn’t know how to begin to...”

The Chairman turned to the Lack of Engagement Officer who had materialised at his elbow, and took from him the case filled with Widger’s bone map. He held it out to Mandi.

“We know you know how this works. Go on, take it! As a gift!”

Mandi cagily took the bonelines from the Chairman.

“Now smash it. That way neither you nor anyone else will raise or find these wretched things again. Rational commonsense will prevail and family life be restored. Or keep the map and we will send your mother and father back to the digital void from which they have come.”

Digital void? Anne and Bryan looked very flesh and bone to her. But if Mandi destroyed the bonelines, the Hexamerons’ savage rationality would finally have won; despite all their stupidity, gracelessness and hypocrisy. Mandi would have given them victory. At least, she thought, that’s how it works in the stories, but this is just a part of Devon, and she cast her eye over the strangeness all around her. Who was to say what of all this had meaning and what didn’t?

“A few weeks ago,” she said, looking carefully and quickly at the map, “I would have let them stay in their limbo, people are idiots after all, what difference is it to them whether they live in illusions or with real things? The difference is metaphysical. But I have learned from my three angels that the real is far more real and full and different than I could ever have possibly imagined. How can I condemn anyone, least of all the people who raised me and tried to teach me the same thing, to that lie? If I had not met you, Mary, Apollonia, Sidwella, I would have happily saved you; but what you have taught me and shown me has fucked you up totally. Real is more real.”

Mandi smashed the bonelines map against a low wall. Glass splintered into a bed of Anemones; the bones bounced across the path and mixed in the blades of the lawn. The angel-priestesses faded to dark shadows of themselves, their revenant outlines barely visible under the bruised clouds.

“You’re welcome to her!”

The Chairman dropped his arm and Anne and Bryan raced across to Mandi. They stopped a few short steps shy of her and of the rapidly fading revenants, momentarily daunted by Mandi’s changed appearance and the fading trace of angelic shadows. She seemed so tall to them, no lesser a figure than the giant supernaturals.

“You’re not dead!” Mandi blurted.

“We’re part of something we don’t understand.”

“What happened?”

“Distraction. Deception. Dark forces...” said Bryan airily, tugging on the beginnings of a beard.

“We’ve been worried sick about you and the camp.”

Mandi noticed that her mother’s clothes were torn and grimy; she had always been an immaculate, if modest dresser; now she looked as if she had been held a prisoner, or forced to wear someone else’s skirt and top. Her hair had been dragged sideways.

“I sorted it out, Mum. They’re all fine...”

“O, thank you, dear.”

Out of the corner of her eye, Mandi was aware of a blue car making uncertain headway up the driveway to the hall. Another no-brain employee letting their phone do their thinking for them. The grid of buzzards and starlings, almost consumed by purple-black clouds, shifted at the edges. Afar off, a pheasant clanked.

“I thought you were both dead! I dreamed of you dying!” she accused.

“We died a thousand deaths, Amanda...”

“You never called m...”

The blue car swerved out of the driveway and ploughed through a border of Asters, jumped the path and smashed into Anne and Bryan, hurling them thirty metres past the Wisteria and into the pile of rubble fallen from the facade of Mandun Hall. Anne’s head was almost torn from her shoulders, Bryan’s skull broke against the remains of a pillar and brain matter spilled down its polished granite. Mandi hoped, for one crazed moment, that the bodies might crumple to empty containers, like punctured balloons; but they held resolutely to the fatty, stringy mess of their ugly brokenness. Hope evaporated and she screamed a howl that chased after it.

The car had come to a halt against the steps to what had been the main entrance. The passenger door swung open, scraping along the bottom step. At the same time the driver’s door was flung open, and simultaneously two figures, a middle aged man and woman, levered themselves unsteadily and manically from the car.

“O, Mandi, Mandi, Mandi!” they chorused.

The woman, dressed in denim, held the roof of the car for support and then pushed off at a run towards Mandi. Undaunted, by the angels, she ran up and hugged her, almost pushing her off her feet. Mandi smelt an overpowering cheap perfume. The man, in tea shirt, pool sliders and shorts, was in close pursuit and embraced them both, wrapping his long, hairy arms around the pair. His smell was male and feral. Mandi could barely shake off the shock to bring herself to struggle; after what might have seemed like her welcoming response she conjured violence from somewhere and pushed the pair savagely away.

“What the fuck?”

“Mandi, Mandi, Mandi,” the woman spoke very quickly and accelerating. “We’re your real parents, we’re the ones who found you on the beach. Those bastards took you and kept you in the dark for thirty years, but we’ve been watching you all this time...”

As she spoke, she ran her hands nervously down her jeans. She bent forward and her lanky ginger hair began to hide her eyes. Beside her, the man had his fists clenched and he shook them in puzzled emotion; with the toe of one slider he was nudging one of the scattered teeth from the bonelines.

“...we fetched you from the beach. We were the two who actually found you there! We wanted to adopt you, but the bastard authorities... anyway, anyway... we waited all these years for this... to have our little girl back... and we know who your real...”

The first arrow entered one cheek and exited the other. A second struck the woman in the side of the skull and sent her whole body cartwheeling along the cinder path, while the two arrows that struck the man in the back pushed his belly forward and dragged his legs backwards, pitching his body stiffly onto its face. The white snipers reloaded as a puff of dust rose from the woman’s hair. Blood sprayed from the man’s lungs. A gasp, like that of a long monster, rippled back along the vale and up into the hills.

“What the Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away,” quipped the Chairman; the execs at his right hand looked queasy, but ecstatic.

The angels opened their wings and they stretched further than Mandi had ever seen them go before. Whatever the magic the Hexamerons had hoped to perform, it had only worked partially. Now the angels’ dark shades flexed and expanded, and as they telescoped their wings, they seemed to suck in the last silvery beams of the daylight and blast them back out. Like a giant car bumper caught in following headlights on a dark country lane. Mandi rested into their feathers as something like insanity seemed to rise up inside her, smacking her stomach aside and washing everything except itself out of her head. Mandi felt like she was levitated; that she was hovered above the old Hall, that she could see the sea and all the darkness in it. She realised that the pain in her chest was not an arrow point but she had forgotten to draw breath; and as she inhaled the chilling air she felt the darkness enter deeply with it. Thin tendrils of blood ran to the edges of her and questioned the borders, something with long arms and many mouths picked at successive images of everything she cherished. The teeth dug in, the mouths pulled apart, Mandi felt her body come apart like a wave breaking on a beach and then draw back together as the waters receded. A mermaid’s purse washed up on a beach, she was dry and shiny and hard and she raised her arms to the black sky and let loose a ferocious shout.

The white snipers lowered their crossbows from the shoulder position, each arrow point was aimed to where they guessed the soft organs of Mandi and the angels might rest. The Chairman raised his arm. The horizon exploded.

Chapter 62

“Ah, theory and practice,” sighed the caretaker, breathlessly, “never works out in the field the same way as at the desk”, hanging on to the edge of the mobile home as it began to swing around in a vortex. Protected by the gentle rise to the disappearing railway tracks, the caretaker’s chosen lookout had fared better than the other caravans and even the more permanent structures; all of them uprooted and set off towards the Vale Without Depths. It was a lonely flood the caretaker was rising on. He had expected the end to come quickly and singularly; instead the waters simply kept increasing with each wave, it was the highest of spring tides, and now with the storm surge came the winds picking up behind the waves. There was nothing apocalyptic about it; it was just happening like shit and beauty.

So, he thought.

Then She rose. A solid wall of unsolid; a melting mirror held in a frame of foam. He knew what was inside it – nothingness – but its surface was as dark as anchovy on toast. No, Marmite! He laughed like a drain. A sickening, salty sheen, rousing itself to the vertical, a horizon tipped on its end, an ocean like an erected sheet on strings of steel, the flat puppet of the deep performing, the curtain of water itself the star. There was no point in crouching, all would be done in seconds. The mobile home was dragged towards the ocean by the backdraft of the giant wave. Like the sudden in-breath before a tsunami, the trailer was drawn across what remained of the railway and above the drowned dodgems and amusement arcades, over what remained of the dunes – and that was little – and down a bubbling beach towards a hinge of land and ocean fury. He was riding that trailer like an ungainly surfer.

His legs braced to take the tipping and rising, the home still holding its shape as the season’s shampooed mattresses and clean sheets played dancing games in its rooms, the caretaker stared into the mass of water for some sign of where She might be within. There was nothing. No clue, no gift, no vision, nothing. “Ah”, he thought, conclusively, as the flat of the waves thudded into his face and slammed his jaw into the back of his skull, twisted his arms around his back and his legs up and above his head, and jammed his spine spherically, “that’s nothing, She’s...”

As the waters took him, on the other side of the estuary and braving the highest point of the sea wall, a gang of teenage boys, watching the rollers entertainingly swamp The Sett, witnessed the caretaker’s elevation and transfiguration into a shoal of pieces. A promising gymnast, an impressively continent young drinker, a wise ass and a secret but unrewarded devotee of Jesus; after this, nothing quite turned out as they expected.

Chapter 63

In the chaos at the rear of the Hexameron Essay Society’s forces, as the first waves of the storm topped the peak of the low coastal hills and fell into the Vale Without Depths, caravans and trailers swept along in their vanguard, Mandi and the angels made their escape. The Hexamerons did not ‘do’ chaos well. In panic, their elites sank back into the spectral embrace of Athelstan’s Saxons while their briefly ordered employees ran for their motors. The hunt struggled to control its packs. The white coats of the programmers were progressively stained.

For Mandi there was already a track. The route taken by the burning wheel over the estate boundary across the field and through the trees, Mandi now took in reverse; her angels following. It was a while before the Hexamerons registered the disturbance in the avian grid. By the time they noticed the escape of their enemies, half of their forces were knee deep in sea water. Those trying to escape in vans and SUV’s were digging their way deeper into submerged mud; huge blossoms of red soil opened up around their entrenched vehicles. Regrouping on the higher ranges just below Mandun Hall, their elite formations were affected for the first time by the rising winds. Isolated trees began to topple around the edges of the estate’s parkland, wires between the pylons swung violently and played odd fluctuating notes as if an electric Pan were weaving mayhem. The grid of birds had been engulfed by low cloud.

“What difference does it make?” yelled the Chairman at the fringe of lieutenants and white snipers. “What did you ever really get from the birds?”

While the Saxon spectres, mindless of the waters, swept across the fields of the Vale and towards the Western slopes of Haldon Ridge, followed like hypnotised rabbits by a rag-taggle army of those office workers and maintenance staff who had escaped the surge, a tighter brigade of Hexameron leaders, CEO’s, scientists, mounted huntsmen and huntswomen, packs of hounds and black dogs, and white snipers set out after Mandi and her sisters. In a second contingent, Grant Kentish and his followers, remarkably self-possessed and steely amongst all the wallowing and drowning, swept up the hill. Kentish’s cloak barely rippled in the storm, his fedora majestically sealed to his scalp. His gang flowed with an unearthly blueness through the darkening, like sodium lamps obliterating the remaining colours of the flowers and hedges; Janine, scrying in her powder compact, pointed the way that Mandi had gone.

On the footpaths, the angels were even more human than before; sliding in and out of divinity. The numbers of their fingers changed; Apollonia looked gorgeously male, chin chiselled like a movie star, then with a shake of her hair she was equally gorgeously female. Mandi needed them, but she was suspicious of seduction.

“It’s just what they do,” she comforted herself under her breath.

And it amused her that she was leading them now. They were not far from the tree of a thousand condoms, but now, Mandi decided, it was time to take the tracks she did not know. There was something too odd and exhibitionist about hiding out at a dogging spot. They needed spaces with subtler signs and more oblique energies; perverse routes that psychologists would never guess. Being with April, Mandi had learned a super-sensitisation to the terrain. The meaning of moss, the songs of the birds or the incline in the hill were all still mysteries to her, but she was beginning to feel things about them, intuit stuff. Just as she had learned to manipulate the big shots at work, to bend their assets against them, to bring down the mighty by a strategic withdrawal of affection, so she was learning the irrational ways of her own land. To feel the give within the take of things. She had always been this person; but only now was she becoming it, far and free from exchange and management.

One other thing she knew for sure; hobgoblins were real. Once you took it for granted that what you saw in the corner of your eye had a usable meaning, then the obvious and the close to hand – the shapes and patterns and tangles – all became thicker, deeper and more responsible for themselves. The path became a partner in your escape, a co-conspirator in your strategy of avoidance; a field of awareness ran all around rather than just ahead.

Mandi was enjoying her new post as commander of angels: as she loped they loped, as she crept they crept, and as she stood and listened they did the same. Witnessing the murder of two sets of parents in a handful of minutes had barely affected her. But she had not blocked it out, she had look at it head on; and in the moment she had made herself someone else; she was a mutant, she was sure. There was something very wrong with her.

Subtle things became plain. A slight darkening in the shadows where a footpath had been allowed to grow over, a fractional contrast to an animal track that would quickly run out. When Sidwella lifted her scythe to sheer away some brambles, Mandi placed her hand on the shaft and quietly led them around the obstruction, careful to hold back the branches, picking up any shed feathers, ducking down a lane that had been walked for centuries being subtly lured recently into disuse. There were malignant forces at work.

At one point the trees to one side of the path opened up and the vista ran all the way down, over the fields and parkland of Mandun’s neighbouring estate, to a small seaside town. As Mandi turned away to keep up their pace the sea swept in and only the church spire on the very inland edge of the town was left above the water. Mary remarked the loss, but made no comment to the others as they pressed on.

That was the other big thing; there was a trace in the landscape. Something in the shaping of things; transitions from one kind of green to another, curves that ran too far to be natural, a narrative in the path, the invitation remaining where a portal had been removed. Despite the gloom of the storm and the raging tree tops, the delicate overlaying of layers – historical, architectural, organic – was increasingly illuminated for Mandi. The angels cast a kind of light that illuminated different shapes of ancientness and from the shadows they helped the trace of things that were very old and huge and extensive to pick themselves out from the green and brown of the ferns. Mandi had always hated the nostalgic nationalistic bullshit that permeated her parents’ milieu; of Olde England and, god help us, the ‘Celts’. Picture book nursery rhyme crap. How had she become a latter-day sucker for Old Dumnonii, magic-peaceful primitives who had failed to learn any decent architecture even when the Romans were building it in their faces? Un-monumental, close to natural contours, chancels in the corners of terrain; there was something in the way the shadows bent, in the stream’s bend; something that was still looking out of the cave and down from the hill.

By steep and narrow lanes and a climbing path that was old but ill-maintained, Mandi and her angels quietly put distance between themselves and Mandun Hall. Vaulting a new fence blocking the unsigned entrance to the path, they clambered up a short bank and onto a wide metalled road. It had a bad feeling, Mandi thought. All her attentiveness to the terrain and it had only brought them onto a long, wide road, stretching off in both directions, flanked by wide green verges and crowded by tall trees. It was too exposed. Why the angels were comfortable to walk it, she could not imagine. A pair of pillars, constructed of immaculate ashlars, set a few metres back on the verges, suggested that there was aristocratic appropriation from way back. The straightness felt Roman or older; the route of a trade at odds with the place. To one side of the long stretch was a villa with a tower that did nothing to ease Mandi’s suspicions. On top of the tower was the dome of an observatory and Mandi had a bad feeling that the Hexamerons would have been involved here, hiding chickens in the cupboards and mixing vigils of astronomy with disrobing for some old goat.

“They did not set out to become that,” said Mary. Her red hair fell across the shoulder of a wing. “They were seekers, excited when the scales fell from their eyes and they could look at things rather than old books, when they could describe to the future what it would think rather than take orders from the past. But they were not satisfied with overthrowing gods; rather than let the Old Ones have their twilight, they dreamed of making a new dawn, and when they failed, when their theory of everything turned out not to include their own immortality, they planned to neutralise the universe rather than reverence its chaos. Now, their games with magic have turned serious; they are seeking a monster to swallow all things. A total destruction to clean up what they see as their mess.”

“Is that why you’re here? Is that why She came to the Hall?”

Just within the first row of trees, were the outlines of a huge earthwork, running off into scrub.

“Who knows? Maybe it was the depredation of the ocean, the rising temperatures, something to do with Brexit and all the hatred that threw up, the growing tyranny of various regimes...”

“The Hexamerons have monsters too?”

“They have an idea of monsters. Hence the magicians. They want the magicians to make them a final monster to end everything. That’s their idea of perfection now; a universe falling prey to itself. To pass off their psychopath-theory as an ideal.”

“Only their elite know of this intention,” Apollonia elaborated. “They tell the lower ranks it will be the unifying of sexual, creative and entrepreneurial energies...”

Water ran in thick streams from Apollonia’s mouth and stained her chest with silt. Sidwella began to cough up sand.

“Don’t think your sensitivity to the path is sufficient, you need to be worshipful,” Mary wagged her wings, her face was stony and there was a lichen green and orange blemish on her cheek, “the problem for humans is that they invented gods and tainted worship. By worship, I mean extravagant love and extreme submission to the being of the world...”

“Don’t waste it on gods!” Sidwella spat another mouthful of sand onto the tarmac.

“We know what they’re like,” bubbled Apollonia.

“Those who do not submit to being,” pronounced Mary, raising her wings and pausing in the middle of the road, as if she addressed listeners skulking somewhere out beyond the earthwork, “are killers, for being is greater and more deserving to be reverenced than masters. Reverence is not reassuring, reverencing has no product, nothing is exchanged or made by reverence, reverence is wasteful, unreplacable, unreproducible. If you can live in the poise of worship you will do well in the next few hours.”

“Poise?”

“To fall before being, to bow yourself, to look at the ground of your existence, reverence the dirt and filth in which your walk, worship that... don’t tell that to any gods, the fools think we are worshipping them!”

The three angels laughed and the trees shook as if a factory of gongs had fallen in a storm; even the raving treetops resonated for a while with their cheers. Mandi noted how wet and straggly the angels’ long hair had become in the long climb though the trees. Then there was silence. As if a switch had been flicked. Sidwella and Apollonia shrank back. Silty water splashed to the ground. Mary sheathed her wings, her expression grew stonier, she swung around to face the direction they had just come. Just beyond the observatory tower was a phalanx of private security vehicles, blue lights flashing silently, flanked by platoons of men and women in hi-viz jackets swinging a single delivery of identical maple baseball bats.

Swinging around to face their direction of travel, the road was now occupied by the Hexameron elite; the Chairman and his acolytes, the white snipers dangling their bows over their shoulders, the pack of giant black dogs dwarfing the humans, eight ancient life-sized and featureless wooden dolls pushed on trolleys by museum staff. All around them, just within the trees, were the shades of the Saxon army holding their axes and spears, two-handed, above their heads, shields slung around them; a few wore helmets, but mostly bareheaded and roughly shaven. As Mandi and the angels turned about them, the forward ranks of Saxons were joined by row after row of soldiers, each line carrying heavier and more misshapen weapons. Until in the far distance, dark within the trees, gangs of archers appeared, feathered arrows in their quivers, and braced themselves in the firing position. All were burning with certainty.

Flanked by the modern hunt, the shade of St Athelstan rode through the Hexameron elite, who each in turn held out their fingers to touch the flesh of the King’s hand. Even the giant dogs nuzzled at his long green robe, jumping up to touch the thin cream surcoat decorated with a golden cross pattée; the points of his simple crown were shining golden spheres. Across his lap he balanced a prodigiously broad, double-bladed sword. His soldiers shook their weapons and the clanking and grinding rekindled the sound of the storm so all above was roaring and wiping away. Fresh spring leaves were torn from the uppermost boughs and fell about the King.

Sidwella broke ranks.

“She’s a Saxon princess,” Apollonia whispered to Mandi, “it’s a bullshit story, she’s really a Celtic water goddess, but that’s another bullshit story; so, now we find out which bullshit is strongest, or if it’s all about something else!”

Blood was proudly running down Sidwella’s back from a wound that had opened up across her neck. Instead of the straggly wet hair, her wild blonde locks had wrapped themselves into two long plaits. As they coiled and pointed, felt and reached, Mandi felt an odd pang of attraction and vulnerability; she wanted to be held by them, and she was unsure who her feelings were serving. When Athelstan shifted his reins and brought his cream steed alongside Sidwella, Mandi began to sweat with jealousy. She felt herself brace, ready to do something she had not yet thought of, and as she did, the forces in the forest took a step forward; their collective stride sounded like a hundred thousand drums beaten once.

Sidwella sensed Mary coming up on her and swung the scythe in a long sweeping arc, but Mary was too quick and fluid for her. Mary flowed around the arc of the blade and then moved in, holding the thorns of her rose stem to Sidwell’s femoral and brachial arteries, and releasing the serpent into the weave of her plaits so that Sidwella’s head was jerked backwards onto the top of her back exposing her pumping jugular.

“Some virgin,” thought Mandi.

Athelstan’s horse reared and backed away, scattering the Hexameron elite. Sidwella was defenceless; the plaits fell out of her hair, her scythe rattled onto the macadam, her sudden regal elegance bent in two. Mandi wanted to close her eyes, but she was frozen; she waited for more blood. But Mary withdrew the rose, and the serpent fell from Sidwella’s hair onto the road alongside the scythe; Mary knelt beside them, picking up the scythe and offering it, and her neck, to Sidwella.

“There can only be three sisters,” Mary pronounced, “destroy me now and you three can be powerful once more.”

Controlling his horse, the Hexamerons flooding back around him, Athelstan steered his horse to Sidwella’s side, then caught up his sword by the blade and held it out in invitation towards his Saxon princess. Sidwella stepped back from the sword in horror, as if waking from a nightmare. Mandi knew immediately what had happened; like her, Sidwella had been reminded by the King’s gesture, turning his sword into a Christian cross, of the pub sign they had passed after being turned away from the cave, a copy of the cover art for a paedophile authoress’s Arthurian romance about the overthrow of pagan goddesses. Sidwella helped Mary to her feet. The three angels clustered together, and once again their wings opened in a collective shielding of Mandi as if they expected the attack to begin. But things would get worse first.

Mandi had forgotten about Grant Kentish. Now, a fanfare of reversing vans greeted the arrival of The Old Mortality Club. The security guards cleared the road for their entrance at the head of a Roman legion, fasces flag and colours flying frantically and tall shields giving them the appearance of a single machine. The iron points of the Roman javelins already smelt of blood. Kentish danced before the wavy sun-beam shapes on the soldiers’ shields, brandishing his fedora, as if he were now the Solar God, the burning wheel turning everything.

“Think,” Mandi told herself, “think!” But all she could think of was her fear, and her visions of the non-existent car crash peeling off the faces of Anne and Bryan, and how trivial that now seemed in light of what she was about to suffer. Kentish, the Chairman, Athelstan, and the Legatus Legionis of the Romans; was there any way of setting them at each other’s throats? More likely, they would each take one of the angels.

The ground shook. It was deeper than the raging of the storm. The various forces looked about them; the angels exchanged questioning glances. The shivering grew more rapid and was now accompanied by a deep booming rumble, there grew a frightened certainty that this would be the most powerful force to join the field so far. For the angels, this might mean escape, or the beginning of crushing defeat. Then a new sound, as if a giant were screwing up paper bags the size of tower blocks. Trees, already shaking in the fierce wind, began to bow and jerk, followed by the preliminary signs of the coming force.

Shadows at first, despite the general gloom, big enough to block out the miserly light. Then the things themselves, as tall as palaces, thirty twisted colossi marching in two lines; their few flowering buds worn like crowns on their vast dry trunks, spirals of lifelessness. Walking chestnut trees. Their step was a kind of drag, their roots as desiccated as their limbs, their locomotion illogical, wrong, at odds even with the forest. They kept to the design by which they had been planted; a forgotten purpose they had stuck to, even in their final shamble. They smashed down living trees and smothered shrubs as they passed, leaving a trail like that of a monstrous slug, spilling sap for slime. Here and there, their dark claws and serpent boughs pulled down the tops of the living trees and threw limbs to the ground, scattering Saxon soldiers. The Roman legionaries held their shields above their heads. The dead chestnut trees were indifferent to the battle; marching through the ranks of scattering Hexamerons and disappearing into the northern reaches of the forest. Somewhere there was a dual carriageway beyond the trees; Mandi wondered what the drivers would make of the arboreal giants. The sound of their progress intensified as the last of the two lines of arboreal cadavers disappeared into the green, dragging the uprooted woody cephalopod maw, and then was gone, swallowed in the storm.

There were more people in the trees, now, revealed by the passage of the dead trees.

Where there were traces of earthworks stood a tribe of the strangest sort. There had been a kind of unity, despite their contrasting styles of weaponry, between the white snipers, Saxon warriors, legionaries, CEO’s and modern hunters. These arrivals, however, were unlike anything so far lined up around the ancient road. They wore dull diamonds and soft zigzag stripes, their wool garments made them vague and undifferentiated; and though it was mostly the men who carried the long swords and javelins, the entire tribe made up their force, sons and daughters woven into the centreless mass. Some tall men stood out for a moment and then seemed dragged back into the simple patterns on their outer coats, while the women carried sharpened spindles, some still wrapped around with whorls of wool, as if they had been surprised in the middle of an unexceptional day two thousand years ago. Even the young looked with drawn faces; pain was their daily ally against indifference. Fingers moving along the shafts of their tiny weapons. The Dumnonian children, faces red from the soil, looked with wonder at the eight huge wooden figures on the museum trolley, like kids in a store eyeing the latest toys. The museum staff backed away, hiding among the white-coated technicians. The Chairman ordered the figures taken and disposed of and the staff reappeared and began to drag these replicas along the old road, hopelessly, aware that their museum stores would have been inundated by now. Once out of sight, they threw the figures and the trolley beyond the verge and headed off towards the dual carriageway in the hope of hitching a lift to safety.

At the sight of Athelstan and his Saxon forces, their nemeses, the Dumnonii bristled. It seemed that the time of fully-fledged physical combat had come, but then the Romans did something unexpected. On seeing the materialisation of the Dumnonii, the people of their occupied territories, and on an order from their Legatus, they lowered their shields and gave an uneven salute to the folk who had become their neighbours. Hands touched brows, some flung out an arm, and then on a second command, sharper than the first, the shields were gathered up, the soldiers turned about, and, to the consternation of Kentish their Solar King, they marched away back up the road they had come, scattering the yellow jackets of the security guards into the trees.

The solemnity of the Romans’ withdrawal was somewhat undermined, when, just before they passed out of sight, the phalange split and the men dived into ditches either side of the roadway. Up through their middle drove a convoy of cars; aged family saloons and the primped rides of old-boy racers. Racing up the road towards the angels, scattering security guards, the cars swerved in unison onto the verge, chewing up the turf and spilling their occupants onto the road. It was Danny, the Julie Goodyear look-alike, her muscle-bound consort and a motley crew of other doggers. To Mandi’s amazement, they joined her! Incapable of explaining themselves even to each other, they had felt called, stronger even than the thrill of encounters with strangers; that was all they could say. There was no time to ask more questions as new reinforcements began to arrive and gather around Mandi and the angels; all the while the enigmatic Dumnonii, silent and watchful, held their ground under the manic trees.

Hyenas were the first, in pack after pack, loping and grinning in an unamused way; immersed in the mass of them, a tall and driven man, straggly-bearded and wild-eyed, a hair parting as thick as a classroom ruler, greasy locks in two unequal waves, his coat tightly buttoned and a crumpled black dicky-bow hunkered down at his throat. He carried the massive jawbone of a cave bear in one hand; an Old Testament warrior come to draw a flood from the sands. The snarling of the hyenas curdled with the complaints of the storm. Thunder roared around the forest. Hobgoblins with the appearance of thick and hairy children walked with their knees bent the wrong way, fitfully assembled, furious and impatient for action, pushing at each other and withering the ferns with hard looks. The Dumnonii children gazed in amazement that these familiars would display themselves so openly; their parents smiled at the confirmation of their dreams. The hobgoblins strutted about, eyeing the road for pilgrims to trip. Around their heads circled fireflies, at which they took intermittent swipes. A circle of something shy danced around the goblins and then widened their fête to surround all the assembled forces, whirling about the trees like tiny particles; while something stranger with rabbit’s eyes in its breasts strode four metres tall and as thin and bending as the trees, and smaller things that switched between hare and man.

A rivulet of adders collected at Mary’s feet, snapping at her own serpent. While around the horses of the local hunt, sending the hounds into frenzied howling, rode a rancid force of wild hunters, their eyes pitted and their jaws unhinged, their horns the rusted parts of old motors, holding at their head a banner with a female figure painted in the centre of it. No sooner had they appeared than they fled at the first flash of red eyes, the black dogs recognised them as charlatans; whatever portent they represented it paled before the prospects of the swelling armies. The storm swept the wild hunt away like leaves in a playground; and swept in wave after wave of compatriots for the angels: blind knockers from the silent mines tapping along the ground with broken props, the Alphington Ponies, the Bocca della Verità mask floated in like the head of ‘Zardoz’, North African slaves from the Venetian galley wreck off Teignmouth at last liberated from the sands, navvies, a flock of herring gulls that landed and complained, a column of narrow headed ants and lost nightingales that arrived in dribs and drabs. Then a saturated Eddie Mann with a gang of other Midlands former-kids appeared from the trees; rescued at Exeter by Eddie and guided around the edges of the flooding. And more and more were joining....

The only new figure that joined the Hexamerons was a young man with a movie camera. Mandi recognised him and nudged Sidwella. It was the meditator from the Retreat House at West Ogwell. He wore the same hoodie and his eyes were still fixed on the ground; Mandi noticed now that he wore the same badge as the Hexameron Chairman, a black disc on a white background. It was a shape Mandi had seen in other places, not just on a badge.

The storm winds in the canopy bent a branch and snapped it; it dragged other smaller boughs into a cascade of greens, striking a Saxon on the shoulder and causing him to fall.

“Is chaos on our side?”

Mandi nodded to the milling of one section around another in both armies.

“I have a feeling that once the Saxons decide to do something, they’ll cut our allies to pieces.”

“This is not a battle between armies,” said Sidwella. “It is a war of ideas. Each player here is a part of an argument. The Dumnonii rarely ever fight; formidable when they do. They are here because they are the life this place is a trace of; they fought beside the Romans at Hadrian’s Wall – that’s why the legion refused to fight them. Unlike the Romans, they never invaded anyone. Why not? Isn’t invasion the organising principle of civilisation? The evolutionary way? Isn’t that what every cultural machine in this county, paper flag for a sand castle or literary novel, has reproduced for centuries? Yet those folk over there evolved an economy that did not excessively exploit their terrain, scorned surplus and took what they needed to live. They built no temples or theatres. Their culture was freely accessible in the natural world which they interpreted as holy, communing with the genii loci of local spaces, from the corners of springs to the depths off their beaches; priests were of no use to them. They valued the unknown over those who claimed to know it. They worshipped what is lost...”

Mandi studied the stoic faces under the trees; beneath lines of pain and smears of red there was a militant peacefulness, an armed content.

“....what had status with the Dumnonii was a reverence for the darkness and nothingness within each person.”

“But they disappeared?”

“Are you sure? Their DNA is in everyone in the county outside the cities. They are not here culturally. Except perhaps in the trace they left in eroded shapes in the land. What broke them was Christianity. For a long time they kept some autonomy; even in the tenth century they were surviving in Exeter alongside Saxons, like oil and water, just as they had with the Romans. It was King Athelstan over there, his project to unite a Christian nation, that really broke them, forced them out of the city. Their descendents stayed in the villages, but they conformed eventually. Not by the sword, but routine. Even so, certain values of Domna prevail...”

Not just the blonde plaits, but the wet straggly hair had gone, the wings were folded away, her scythe leaned against a tree; she was back to the April that Mandi had felt herself falling for once before and now felt it happen again; the luring intelligence of something trying to creep beneath a gateway.

“... a tendency towards peaceful co-existence – there were no medieval pogroms here such as besmirch Norwich or York – and faint echoes of the Old Religion surviving in the veneration of certain female saints and in the eerie feel of places like the spring at Lidwell or the caves. Study the church windows, the old ones, see how many times there are three goddesses, it matters little what their names are or whether they are saints or angels. They are the three consorts of Domna; the two that remain on land to reverence her and the special one taken to the deep with Her. The one...”

She glanced at Mary and then stared hard at Mandi.

“... who by knowing knows the deep. We struggle to contact the contemporary living; most do not hear us at all, not even those who say they believe in us, too busy promoting their own magic. But in our story, our culture...”

This from an angel, who minutes before, as tribute to her Saxon King, had struggled to cut off the head of her sister, the Mother of God, the very Symbol of the Deep! Mary’s robe was now as blue as clear sea water on a sunny day .

“...we are trying to make contact with people in the present county. We have always done this at times of evil – the drowning of the slaves, the Blackshirts organising in the 1930s – times when She brought the storms and swept things away, keeping at bay attempts to subject all to a prevailing idea. For at the very deepest deep of the surviving Dumnoniian spirit is the moment when the Great Squid Mother confronted the Manichaeistic God of perfection and seduced him with the power of place and thing, and thus gave birth to matter without subjection to thought. And that is why the Hexamerons and their Beyondists are so angry!”

Mandi glanced over to the restless Hexameron army. What were they waiting for? Then Mandi thought she saw a ghostly squid hovering in the trees above the Dumnonian troops, dark tendrils reaching down towards the ground, a giant head flopping about in the shaking canopy, then a lightning flash lit up an empty space of writhing leaves. Thunder exploded all around; branches fell all about. The clouds above opened and curtains of rain fell through the leaves, lashing the assembled creeds. In the confusion, an impatient white-coated programmer seized his moment, grabbed a spear from a Saxon hand and launched it in a clumsy arc towards Sidwella’s back. Before it could hit its mark, the white snipers had raised their crossbows and fired off four shots, two each at Mary and Apollonia. There was a series of cracks like minor lightning strikes; the Saxon spear, its shaft was split down the middle, and three of the crossbow arrows skittered across the wet macadam. The fourth arrow deflected from Apollonia’s cheek and took out two of the dogging males, slashing a fleshy part from one thigh and passing through a flabby upper arm, knocking them to the verge. Their fellow enthusiasts gathered them up and dragged them across the mud to one of their cars.

The lightning flashed again. It lit up a scene uncannily like that of the graveyard that Mandi and April had found at the end of their walk. The three angels were stood back to back, against attack from any side, while Mandi knelt in the rain at their feet. She looked up at them; their bodies, clothes, faces were become an unhuman white and giant, they were monumental beneath a layer of plant growth. Moss had settled on their arms, lichen in their eyes, gelatinous algae on their lips; their stone white wings were folded together, the feathers interleaved like a single shield. Upon their brows tarnished stars glowed like street lights in November mist, their hair stood up on end, their weapons were turned to hypnotic flowers and their eyes raised towards the storm as if they could see things better by not looking directly at them. Suddenly they flexed and drove a ripple of destruction through the Saxon ranks. Bodies felt apart, weapons rattled against tree trunks and embedded in them, heads were kicked in all directions by fleeing comrades. Sidwella’s scythe whirled like helicopter blades, the teeth of Mary’s serpent sank into the soft flesh of unshielded ears and tongues sending victims into screaming madness, Apollonia’s pliers dug rib cages from chests and pulled spines out through the backs of necks; soldiers fell all around like empty costumes of skin, shopping bags robbed and dropped by deadly thieves. As the Saxons turned and ran they chose their nearest route of retreat, back down to the Vale, soon breaking from the trees and across the fields, but the waters from the coast were coming up to meet them and they were forced to tack around to the West.

The Dumnonii gave chase, followed by the doggers, their cars skidding down muddy farm tracks and careening across soggy fields, despite their wounded, the blood spattered interiors of the cars like field hospitals. The Hexameron elite, two and three to a horse, raced away along the Port Way before tangling with astounded traffic on the B3912, cutting back down through the moor and crossing the fields above the Lovecraft villages, arcing to rejoin their panicking foot soldiers.

The angels were fixed, statuesque for a while, in the centre of their assault. A circle of evaporating spectres lay all around them. A handful of bloodied white coats were being spirited away by hobgoblins; shattered branches lay under a steaming carpet of fallen leaves, wet and shiny. Down in the Vale below, James Lyon Widger was leaping hedges again, not avoiding the goblins but leading them, his pocket bible thumping against his beating heart, a racing paradiddle, while running beside him were the horde of hyenas ready to launch horrors on any fallen Hexameron. Tiny packs would occasionally detach from the herd to despatch an unfortunate spectre.

“They who have reverence,” said Apollonia.

“Will prevail,” completed Sidwella.

Down in the Vale, fleeing towards the villages, the troops of the Hexameron Essay Society were struggling in the terrain. This was not their place. There were few Saxon villages, few crossroads, few greens for assembly, few manor houses around which to mount a defence. It was a place without walls or ramparts, the only earthworks were ancient gathering sites on the tops of hills, easily surrounded. How were you supposed to defend a stream or cave? For the Dumnonii, rapidly following their own faint trace in the land, the field of battle for them was the same as the space of their sacred plots; strategy was a kind of worship. A sacrifice had begun.

The strange stalking thing with rabbit eyes, the hobgoblins climbing into a mine in one field and emerging from a spring in another, the hyenas with their manipulation of the shadows, the Dumnoniian children running ahead as the fingers of a knowing hand, touching the paths for affordance or resistance; the Hexamerons had no counter troops for these lightning fast adversaries who popped up whichever way they retreated. They were helpless in the open fields where they fell victim to Widger’s packs. They were helpless on the paths where nothing in appearances could warn them of the strange deaths that lurked there.

Meanwhile, the angel trio intuited a map of atmospheres in their shivering feathers and spread it across the swathes of their forces; a trembling ambience by which their troops could feel their way. In a spreading act of geographical and ambient miscegenation the collective premonitions and touches of the thing with rabbit’s eyes and spectres and inspired doggers fed back and became a loop between angels and soldiers, became field-like, planes without continuity, broken cosmic consistencies healed by the faintest trace of elsewhere and elsewhen, drawing the robins in.

As the angelic troupes ranged across the Vale and spilled towards the villages, surrounding and ambushing the pre-medieval hierarchies of the Hexamerons, the clouds of the storm briefly cleared and birds fell from the briefly opened skies in thousands and thousands. Mandi and her angels rushed to support them, crossing the farms of the Hoarfrost Estate and heading down the hollow ways towards the Lovecraft villages. Higher up, closer to the little moor, the Hexameron elite scanned a landscape they suddenly found they did not understand; so open and explicit, and yet every move they made drew snakes and goblins and loping things with faces in their chests from every hedge. When they took a hidden path its sides erupted with snapping badgers, catching at their feet and fastening to their heels.

Dependent on their smart phones, the Hexameron commanders struggled with the unreliable phone signal. When they were able to give orders their commitment to straight lines, targets and achievements, to the fastest route from A to B, left their troops at the mercy of everything from C to Z. Their mechanical concepts of survival, fitness, symmetry and singularity, not only did not mesh with the terrain, but were eaten up by it. Ideas learned from books about desert wars, during their contractors’ urban mopping up operations or from the strategies of anxiety they sold to foreign partners did not fit here, but sent their forces in unreal formations into the jaws of reality. The programme of the Machine had been shared to the devices of their foot soldiers, but the angelic upstarts had refused to get with the rules. The Hexamerons’ options were shrinking away. Their hopes for a great Idea were fading. A long battle looked to be ending prematurely.

The waters that had washed across the Vale Without Depths were spreading westwards, flooding caves that had once been submarine and were again. The storm surge had already broken against the base of the Great Hill and crept up towards the deconsecrated chapel on the top at West Ogwell. The salty water seeped through the cracks in the volcanic rocks and into its curling recesses, where something sealed and dry and dark had begun to regenerate, filling out and pushing itself upwards towards the surface. For the Hexameron troops, all this left only a narrow channel of land along which to retreat and regroup; as the Saxon detachments attempted to maintain their formations in retreat they became increasingly bogged down in open fields or wedged onto hollow lanes unable to raise their weapons or defend themselves against the Dumnonii and their allies who launched stinging attacks from their raised sides, the angels guiding these ambushes with the help of new allies among the recently liberated robins, who invited the angels to patch into their perceptual fields.

Observing from its vantage point, the Hexameron elite rejoiced for a while at the sight of a flock of herring gulls, taunted and tailed exactly by a flight of their rooks. The group enjoyed the extraordinary tailing capabilities of their dutiful avian collaborators, and the possibility that the birds might still hold the key, attaching themselves like warning drones to the angels’ ambushers, until it dawned on one of the programmers that what they were applauding were the gulls’ shadows on the hillside. Scrambled attempts to find the avian grid were unsuccessful, even in the briefly open sky; instead, the sounds of blackbirds, chaffinches, wood pigeons, green woodpeckers and goldfinches singing sunnily to the territoriality and specificity of their spaces returned combatively to the air.

“Chaos!” complained a programmer, holding up his tablet for anyone who would look. “We’re losing our information!”

There came a crack. If the march-past of the dead chestnuts had rattled the ground, this din disturbed the core of the planet and the counterpane of the sky. A deep grinding sound, of two plates shifting along the Stickleback Fault; a screaming, tearing wound of rock as its subterranean layers wrenched out of alignment and fought to right their dislocation. A giant puff of dust rose in a curtain from the High Street of the Bay, throwing its manhole covers over the tops of buildings, splitting the Necroscope Hotel in two (it was consumed in fire) and ripping up the fields between West Ogwell and the Hoarfrost Estate, opening a chasm into which divisions of the Saxons, packs of black dogs and straggling security guards tumbled, cried, and fell silent. King Athelstan’s horse reared on the edge of the fresh chasm, stumbled and toppled in, the King’s head smacking against the side on the way down, his crown ricocheting from face to face, when abruptly the two walls of limestone slammed together again.

The filmmaker in the hoodie had early observed through his viewfinder the opening crevice as it raced through a meadow and had promptly gone scampering up the hill towards the deconsecrated church. Far off, under the Irish Sea, parts of the sea floor fell away. Up above the surface of the sea seemed to give way, dragging a trawler under, before roaring back upwards to form a double wave that would soon inundate the coast of North Somerset and then, two hundred miles to the North-West, devastate the towns of Tramore and Dungarvan in the Republic. The tremors rattled the sea floors along the Bristol Channel and reached around Land’s End to the red cliffs and limestone floors of South Devon; disturbing tiny shrimps and giant mysteries from their lairs of slumber.

As the dust from the earthquake began to drift across the fields, the Dumnonii women shouted and pointed, waving their spindles. A memory of beasts from the oldest days had been released and a brief translucence was modelled in falling red dust: the figures of elk, cave bear, mammoth, wolf, sabre-toothed cat and mountain lion were briefly returned. James Lyon Widger let out a violent “huzzah!” The Dumnonii hunters licked their lips, while the Saxons fled at the sight of things they thought exterminated. High up on the hill at West Ogwell, a part of the hillside slipped away; a landslide that revealed a shiny, wet, black wall of something that was moving and pulsating, its texture as strong as a hard plastic, but rippled like a puckered slug. The boy in the hoodie ran up and touched the black surface with his hand, it touched him back, and he began to shout, calling the surviving remnants of the Hexameron forces to muster to him.

Like lost children suddenly hearing a familiar voice, the remaining brigades of Saxon soldiers, a stray black dog, the whole of the local hunt and its hounds, a security van bouncing down the farm track at the bottom of the hill, a muddy and miserable group of Old Mortality sybarites with Grant Kentish at the head, his fedora squashed and cape in tatters, and then the dribs and drabs of the trailing employees of the Hexameron companies in their hundreds, a growing crowd of frightened combatants, began to gather before the boy in the hoodie. He stood authoritatively before the dark thing in the hillside, it was making the shape of a featureless eye; the touch of the thing and the surge of power from the angry planet had filled the boy in the hoodie with certainty and vision. He saw it all now, and others would see it as he saw it. His eyes shifted commandingly across his gathering detachment, while under his breath he was casting a spell to bind and destroy his enemies and secure him the leadership of the Dark Hexameron Revolution.

Chapter 64

Mandi followed the angels as if she were walking in a nightmare. She had somehow compartmentalised whatever it was she had seen slaughtered on the lawn of Mandun Hall. After all, she already thought that Anne and Bryan were dead, and the new ‘parents’ who had appeared, who were they? So, in the end, to her way of thinking, no one was alive who had been dead and no one was dead who had been alive. It was not so easy, however, to box up the slaughter of the Hexamerons’ dupes, no matter how malign and stupid they were. It was the transience of it all. The cold trade in spectres and the fragility of limbs was getting to her. Nothing connected by nature need stay that way. All could be decapitated on the orders of mayhem. What was the point of anything? She was not a soldier. The angels had taken their opposition to the Big Idea too far; their love of things was the cause of too much dismembering.

The coldness of the quantum thing was worst. She felt the shivering of probability and the agitation necessary to hold the super-positions free of collapse, but there was as much a removal from the funk of things as there was immersion in its below-base matter. Wasn’t it al the same inhumanity? How they would laugh at her in the office for her sentimentality, but too much that was fundamental was being rocked for Mandi. So, lamely, hating herself for it, she tagged on resentfully behind the three drowned sisters as they burned their way across the fields. She felt their disapproval; she was a chink in their armour and they let her know it. If she was honest with herself, she felt the same way. She wished she had her Remington, or her caretaker.

Skirting the Great Hill, a space too easily surrounded, the angels followed quiet lanes, their great height enabling them to see over the hedge tops; their communion with the birds providing them with coloured diagrams of their enemies’ locations. Avoiding a disoriented but still dangerous gang of Saxons, they slunk into the next valley along and Mandi recognised the pub with the faux-Arthurian sign; she longed to visit the church and sit before the paintings of the female saints. She was surprised by the indifference of her angels. What she thought was important, might not be so at all. Past a tree shaped like the skeleton of a leaping horse, and then through a gate, they found a way along the bottom of the valley beside a long flat field. Mandi was anxious. She was uncertain why; then it struck her that the storm surge might find its way this far inshore where the land lay so low.

As if she made the thing appear out of her own anxiety, there in the middle of the flat field, surrounded by retreating waters was a mobile home, swept in at the head of the storm surge. It was, inevitably, her home, Anne and Bryan’s extensive trailer.

She climbed the fence into the field, unpicking the point of barbed wire from her trouser leg, and ran headlong at the house. The front door seemed remarkably solid given the journey the whole structure had just taken. It opened easily; she remembered its feel. She had not locked it when the angels came to call for her. Inside, there was more than she expected, more than there had been when she had left. It was not the disappointing shell she had first returned to from London, stripped of all her things. They were all back now; her drawings, her magic objects, the shelves of favourite books read over and over, the weird charts she got from ‘sending away’ for stuff, her ‘Misty’ comics, her clothes. She tried a few, but she must have put on weight; she felt uncomfortable in them, as if they were not really hers. She was an impostor, pretending to be herself. It was usually at a time like this that she sought out the whisky bottle, but, supernaturally, the thought made her feel sick. This was an odd kind of coming home.

The curtains were drawn; that was it. Like when someone dies and before the hearse leaves the house. But she dare not pull them open, for fear that Lost Horizon would be there, and the whole thing – the thing in the sea, the saint with the smashed mouth, the walk with April, the momentous battle they were in the middle of – had never happened. It was a dream she had just woken up from. Except she had not just woken up; no one wakes up by walking through their own front door. Do they?

If all her stuff was there, so should Anne and Bryan be, but she knew they would not. Still, she checked their rooms. Pushing open their bedroom door, she thought for a moment there might be two rotted things in the bed, but it was the disturbed pillows that Mandi herself had left that way. The journey overland, at the head of the massive sea surge had disturbed nothing; such was the solidness of the life she had assumed was mostly illusions and possibly lies. There was no Anne and Bryan, of course, but there might be one thing of theirs. She dashed to the drawers. Sure enough, it was all there, just as she had found it on her return from London. Even the things that she knew were now in the possession of the solicitors’ office. She pulled out the various papers, then gently eased the folder in which the manuscript should be. Yes, it was there. Maybe this time it would reveal its secret; wasn’t that why she had been called back? Effectively left her job? Seen two set of parents killed? To know!

She drew the sheets of paper from the envelope. It was just as before; the same paper, the same typed script, the same words. She scrutinised every line; desperately, hurriedly. She had a sense of angels outside the door, shadows of wings that darkened the entire trailer. Vision blurred; she used her finger to run along the lines of each sentence.

“That traces of an antediluvian civilisation with its attendant flora and fauna can be so readily found in the obscure lanes, fields and woodlands of this part of Devonshire has long been known to the coarse laborers that dwell in this lugubrious place.”

It was just the same as before. The words, the font, the texture of the paper, the indentations made by the keys. But as Mandi’s finger brushed the word “place” she felt her nail catch on something; a small piece of the full stop had chipped off. She ran her finger over it again and a little more of the full stop stood up from the page, she flicked it away and a small line of the paper’s surface concertinaed and revealed a blackness beneath.

To find some resistance against which to pull, Mandi took the page through to the living room which was unreasonably bright. She placed the page against one of the shelves of the bookcase. She struggled to find the little paper ‘ring pull’, distracted by the books on the shelf. She had never remembered books like these: ‘Rituals of the Black Church’, ‘Satan’s Heroes’, ‘Secrets of the Martyrs of Beelzebub’, ‘Blood Sacrifice: Liturgies’... The spines were decorated with inverted Christian crosses, blood-smeared chalices and young women tied with ropes. She drew one out from the line of titles; Bryan and Anne had never shown her these. She thought they hated this sort of thing; this was what people had said about them. It was not true. Flipping the book open, the pages were blank. She pulled down another; blank again. And another and another – all blank. Mandi hurriedly took hold of the crumbled shard of paper and pulled at it as gently as her shaking hand would allow and the page began to unpeel. The process seemed very drawn out, despite her urgency, as though her limbs were caught in treacle or packaged with cotton wool, but eventually, having reached the edge of the sheet, Mandi was able to pull the whole veneer from the page to reveal a single large black spot, slightly tilted like a disc.

She ran from the trailer and across the field which was now full of stranded jellyfish, looking like translucent cow pats. The angels were standing, statuesquely, on the path.

“What’s going on?” cried Mandi. “Nothing is as I remembered it!”

“Hasn’t it struck you yet,” soothed Apollonia, “that we might have been on a ‘different’ layer of Devon for a while now?”

“What does this mean?”

She held up the page with the black disc.

“That we are going to lose,” said Mary, blankly. “That we have all been fighting the wrong enemy. Even She did not see this coming. Perhaps if we had had the birds on our side from the beginning...”

“What do you mean? A trick by the Hexamerons?”

“They will be the last to know.”

Chapter 65

The young man in the hoodie, his distinctive black disc badge glinting in the last rays of the sun as the purple clouds crowded in above, was addressing his troops through the medium of a hijacked and adapted HoloLens programme. Freeloading on the Hexameron’s avian platform, he had patched his comrades into his website, Tony ‘The Summoner’ Sumner-Crabbe; from where they were downloading an AR app that allowed them to collectively and semi-virtually realise the full size and shape of the black disc he had ‘discovered’ – by various deductions and leaps of faith – buried beneath the West Ogwell knoll. Tony had been an unwelcome hanger-on at the fringes of local occult groups since his early teens; he had attended all the public Hexameron seminars, though none of its members would acknowledge him in public or private. The Chairman had only once responded to his many emails; he had sent an attachment of the black disc that had inspired Tony to fashion his own homemade badge. The Hexamerons never spoke about ufos at their meetings; but Tony could always hear in their talks the voices of the aliens. He understood and believed them when they spoke of evolution as a controllable thing, of the wasted potential of human mental capacities (people had sure as fuck wasted his) and its future realisation; if such things could be controlled and realised in the future then they must have been controlled in the past. Not by humans, who were too primitive then. But by visitors; visitors who – as his website proved – had never really left. They would help humans take the next step; the chasm awaited and they had nothing to fear from it.

Tony threw back his hoodie just as the clouds covered the sun, the better to review the thousands that stood before him, their arms raised in a ‘Roman salute’, their phones held up to the hill, transfixed by the shiny black disc within, part alien technology and part geological stratum, sat like an egg in the nest of a curled black shape in the rock above it. The Hexamerons – at least not the present leadership – had never fully understood the real meaning at the heart of their ideas; but then they had run away from the ‘other side’, they had turned their faces from the black sun and failed to harvest the dark spark that Tony had vacated the shell of his body to welcome inside, the sombre flame that burned away all the Demiurge’s failures and transformed all flesh into the great Alien Idea.

The black eye in the hill opened and it was full of teeth.

“The stars await you. The heavens await you. The gate is open to you. Change defeat on Earth to victory in Paradise. Lead me and I will follow,” Tony tweeted.

On the screens the teeth of the beast flashed like stars in a night sky. The first of the troops began to shuffle forward, still holding their phones before them, like initiates bringing offerings or sacrifices.

“Stop this fuckery!”

Mandi was stood high above Tony and the inky eye. Beside the church tower, framed in the full bulb of giant oaks, flanked by her angels in monumental splendour, their wings spread, their faces flashing bioluminescences of orange and green. Mandi cast her gaze around the terrain. Other than the crowd that the boy in the hoodie had gathered to him, the rest of the Hexameron forces lay in shattered parts, strewn in the lower branches of trees, face down in ditches, piled up in hollow ways. The expensive weaponry they never got to fire had been trampled into mud and cow shit or tossed into ponds. A ring of Mandi’s own forces, reinforced all the time by new creatures – a drenching Cutty Dyer, swan worshippers, sprites, nymphs, dryads, and water horses, things the terrified Saxons recognised from stories they had formerly frightened themselves with – had formed within the blood-drenched fields, surrounding the last remnant of the enemy army. The doggers, tending their own wounded, had made surprising alliances with those who were not really or barely there at all; their familiarity with scrubland and improvised cover, their aptitude for arriving discreetly and leaving suddenly had served them well in the hand to hand fighting.

“Who the fuck are you?”

The boy in the hoodie turned and looked up to the church on the hill. It was the boy that April and Mandi had seen right there, the ‘meditator’ with down-turned eyes. But only now that he looked up did Mandi recognise him as the round-faced conspiracy nut on the dunes, the kid who had dropped the article about birds, a theory that turned out to be something like true. He was no longer dressed in fatigues, but his blond hair and featureless face were distinctive enough. He stood out by his vacuity. He was the malevolent vacuum that had replaced the Hexameron leadership.

“And who the fuck are you?” Mandi responded.

The boy replied, surprisingly.

“My name is Tony Sumner-Crabbe! People online call me ‘The Summoner’! Ufologist, chaos magician, researcher! These are my flock!”

He prodded a finger towards the figures forlornly tramping up the side of the hill to the shadowy mouth in its exposed side.

“C – R – A – B – B – E. Yes, I’m the son of that bastard!”

Mandi knew who he meant.

“He abandoned me, like he abandons all his children. He was a fucking coward, Amanda! Forget him! He did stuff, but he couldn’t be arsed to face up to his responsibility! He left me and my mum to get by on our own; she was his student!!! He should have been prosecuted! If they were in love, why did he leave her, eh? He was on good money! Why did he leave you?”

Tony pointed his finger at Mandi and some of the climbers looked briefly up towards the four figures beside the church.

“Going on pilgrimage, was he? Where to? Up his own arsehole? Don’t look so fucking surprised, you know who you are! Sister!”

“Half-sister!”

“Same thing!”

“No! My Mother is no fucking student of anything or anyone!” And with that fury, Mandi threw out her arms and the air around her seemed to ripple.

“Be careful,” counselled Mary, “his is a magic that eats the soul. See his followers, see how they are lost? His disc beneath the hill, his mirage of your home washed up in the field...”

“That was him?”

“Don’t be fooled by appearances,” Apollonia chipped in, unnecessarily.

“Those are the transferable rituals that destroy all places.”

The first of the Hexameron foot soldiers entered the toothy eye in the hill. Mandi expected a spurt of blood, the sound of tearing flesh, but they walked quietly into the orifice and disappeared from sight. Tony ‘The Summoner’ was wide-eyed in gratified astonishment. Nothing else he had ever done had worked; the universe had been saving him up for its final moment.

“He’s murdering people down there... with his Pokemon Go shit...”

“They seem very happy,” said Sidwella, drily. Those forces yet to join the queue into the hill were waving their phones and cheering. As the light once more failed, their screens shone brighter like fireflies buzzing about their heads. The crowd milled and seethed and then drew back to reveal the four white snipers, their bows slung over their shoulders, their masks pushed up to the crowns of their heads, their white jumpsuits splashed with gore, and bearing in each hand the heads of the Chairman and his CEO’s. They laid the heads at the feet of ‘The Summoner’.

“Can’t you stop this?” Mandi whispered to Mary. “We’ve got them completely surrounded and we’re letting them carry on like this!”

“There is something else here. Something that is guarding their greed for death... do you dare to call it out, because we do not...”

“But we can’t just stand here and watch them!”

“We are statues. Just standing and watching is what we do.”

“I thought you were saints!”

Mandi turned on her heels and began to run down the hill.

“Stop, you fuckers!”

The white snipers had time neither to raise their eyes or unsling their bows, Tony was mid-swivel, and Mandi was within the arc of a leap, when the hill broke. Sheets of turf shot into the air and fell among the Hexameron revenant. Cows panicked, broke down a stile and threw themselves against the wall of the church, rebounding and scattering gravestones. A grinding sound went up, like the groan of a long-tortured prisoner; a curtain was drawn in heaven and a deeper purple gloom fell across the hill. Tony staggered and fell to his knees; the lithesome snipers joined him more coherently. The white of their costumes stood out from everything else, which had taken on the glamour of spilled blood.

Tony screamed above the industrial clamour.

“The second seeding of England!!”

Like a thick stream of volcanic ooze, squeezing itself through the toothy eye in the side of the hill, a cyclopean turd, a slug-like sliding thing heaved itself from the darkness into the gloom, its fanged fringes fastening upon the turf and dragging its mucus-spilling sides down the hill, huge bulges like fat seals fighting inside a black sack struggling beneath the surface and a giant and obscure limb flopping about and pulled along behind, while the eyeless prow ploughed through the topsoil, swallowing the Hexameron pilgrims and their screens beneath its oily bulk. Not quite enthusiastic enough to have been consumed, Grant Kentish danced around the skirt of the dusky beast, waving his fedora around his head in salute to the featureless thing, as bland in its dark way as Tony was in his fair looks. The Slug-Protector of the black sun disc shook itself three times, each time pulling another misshapen lump of lolloping worm-body from its orifice, each time the elongated organism shuddering before settling its skin into a rounded, bulging and embrocated smoothness, before drawing itself up for a fourth and final contraction. With a filthy sloshing sound the Thing spilled from the hill, folding the eye-mouth inside itself as it fully emerged. The pilgrims had been processing into its arse. To be born, the lubricious monster had turned itself inside out.

Like scrapings of leftovers from a plate, the Slug tipped the undigested organs of pilgrims onto the ground, which shook again. The three angels pulled Mandi away, racing in their strange floating-dragging way down the Retreat side of the hill and back along the valley bottom by which they had come. The church tower on the top of West Ogwell Hill shivered and then fell with a crash into a chasm that opened up below, followed by the nave and the giant oaks; the hill belched a grey mushroom cloud of dust. The disturbance in the volcanic rocks had triggered the general plates once more and the crevices that had closed after the earthquake were now opened up again. From their slits issued the Hexameron forces in burned and lava-like forms, their bodies crusted black, their features charcoal and eyes jet. In the gloom they barely registered, but their heat seared the ferns and hedges and some low branches burst into flames, the fires spreading, driving the angelic forces that had surrounded the hill and its blasphemous worshippers towards the West, while the great form of the slithering beast, almost a mile long, further cut the angels and Mandi from their supporters.

Racing Northwards, egged on digitally by ‘The Summoner’, the revived remnant of the late Chairman’s troops, reinforced by obsidian forces with a charcoal Athelstan at their head, strained to isolate and interdict the angels’ retreat. As they ran, the remnant held their phones above their heads where Tony had replaced the grid of birds with one of back-engineered alien saucers, in swastika and Balkenkreuz livery. There was nothing there, of course; but then, by the time Tony had realised his dreams and brought the Hexamerons’ war with being to a close, there would be nothing anywhere.

Chapter 66