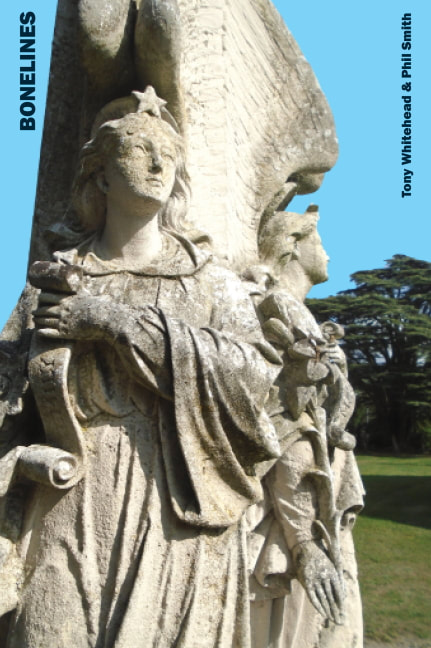

BONELINES

|

A dark novel set in the 'Lovecraft Villages' of Devon, spanning several thousand years, from the time it was occupied by the Dumnonii, through the 19th century to its more contemporary occupation by holiday park dwellers, marketing professionals, doggers and other romantics.

|

|

Publication: 1st August 2020

List Price: £15 Format: ~ Paperback - 362 pages Size: 15.6 x 23.4 cm ISBN: 978-1-913743-06-2 Tags: walking, walking arts, pilgrimage, web-walking, embodiment, Devon, magical mode, drift, dérive, mythogeography, falling, imbalance, psychogeography, improvisation, Tony Whitehead, Phil Smith Buy the paperback (£15)

|

In their Guidebook for an Armchair Pilgrimage, authors Phil Smith, Tony Whitehead and photographer John Schott lead us on a ‘virtual’ journey to explore difference and change on their way to an unknown destination. They create a pilgrimage that any of us can follow, even if we are confined to our homes.

To research the Guidebook the authors went on an actual journey. Bonelines is the secret story of that journey. Given the present circumstances it now appears prophetic, prescient and helpful, so they have decided to bring it into the light. It is written as a novel. Phil Smith writes:

"A couple of years ago, with ornithologist and DJ Tony Whitehead, I began to walk the Lovecraft villages; small communities in Devon, not far from Newton Abbot, where the ancestors of US ‘weird horror’ writer H. P. Lovecraft lived. We were searching for the Lovecraft heritage and a terrain that, via family memory, might have informed the cosmist vision of the writer. We found both those things. But we also found just about everything else. In a landscape where ideas and shapes, symbols, stories and materials are woven together in webs. Maybe everywhere has this kind of intensity if you know how to look. We did not particularly ‘know’, though both of us had been walking in our different hyper-sensitised ways for a while; however, the magic ingredient seems to have been a dollop of trauma for both of us. We would later distil our experiences in a Guidebook for an Armchair Pilgrimage, a focused and disciplined conflation of our disparate experiences, while at the very same time, we abandoned discipline to pen a dark fantasy fiction, Bonelines, which rages around the Lovecraft villages, casting its net wide to catch the multiplicities at work there; conjunctions that, by their very waywardness, mark a way. Our own way was performative. As ambulant researchers we played numerous roles: pilgrim, travel writer, social snoop. There were ethnographic and auto-ethnographic elements; we attended local events and public spaces in order to participant-observe, visited archaeology open days, pagan workshops, chatted with locals in pubs. We walked with and visited individual locals; recording their observations about their area. All the time we noted our own subjective responses to the route while observing its effects on others. However, rather than accumulating data to support an interpretation or describe a phenomenon, we attended mostly to anomalous information; what Charles Fort called ‘damned data’. And we subjected that data to fictionalisation; in order to define the mythos of this place it was necessary for us to write a new mythos for it. Such entanglement of documentation and intuitive creativity is a practice-as-research; findings being generated by the creative writing, adding to those arrived at by reflection and analysis." Companion reading -- Free to download:

From the Preface

The ‘ground’ from which Bonelines rose lies mostly between Newton Abbot, Totnes and Ashburton in the southern part of the county of Devon (UK). There is an anonymity there, the area has no encompassing name; it consists of gently rolling hills, scattered communities punctuated by an occasional Saxon cruciform village, and a complex of often deserted Devon lanes, footpaths and pedestrian hollow ways. ... As stories emerged from this landscape, and as in our long pedestrian conversations we began to flesh out the skeleton of an exemplary fable with elements of a roman à clef, we widened our geographical scope and walked the land between Dawlish and Exminster, around Bovey Tracey and the lower Teign Valley, and the backstreets of Torquay; guided by the unfolding narrative demands of the novel. At the same time we were subjected to an intensity of coincidence and connection that would have been frightening if it had not been quite so exciting. On one occasion we stood on the footpath of the coastal road between Torquay and Paignton with the poet Sam Kemp, discussing the fantasy of subterranean aliens conjured in the novel ‘Vril: The Power of the Coming Race’ by Torquay novelist and imperialist politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton; a few days later the pavement at this spot collapsed into a huge sink hole. |

An example of the entanglement of documentation and intuitive creativity from Bonelines:

The village of Torbryan in Devon includes a mediaeval church, a farm, The Old Churchhouse Inn, and a low cliff running about half a mile pitted with caves. One of these caves is named The Old Grotto by its original excavator, James Lyon Widger, and contains the remains of a medieval chapel. All these, according to drinkers at the Inn, are linked by a tunnel. (Aren’t they always?)

There is, surprisingly, no mention of this cave chapel in parish or diocesan records. This omission, and a suspiciously similar engineered rock fall blocking its entrance, led the archaeologist F. E. Zeuner to suggest that ‘The Old Grotto’ might be of similar nature to a contemporaneous chapel in the north of the county closed down by the church authorities for worshipping “proud and disobedient Eve and unchaste Diana”. Inside the cave are limestone formations that look like tentacles.

A chapel in a cave with submarine connotations (a river once ran through it) and a possible link to unofficial worship of unusual female figures dimly chimes with the local Iron Age worship of Dumna, a goddess of the deep. An earth monument of the Dumnonii people on top of nearby Denbury Hill is framed in the mouth of ‘The Old Grotto’ if you strand in the cave and look out.

Mediaeval rood screen paintings in the parish church in Torbryan include Catherine who was prone to mystical “ravishment” during which she went stiff as a board; Margaret who was swallowed by a dragon; Ursula, a Dumnonian princess who, inadvisably, led 11,000 unarmed handmaidens against an army of Huns; Barbara who opened a portal from a tower to a mountain and turned a recalcitrant shepherd to stone; Elizabeth who opened her robe to reveal a vision of roses, and Helena who found the true cross under a Temple of Venus.

Opposite the church is the Old Churchhouse Inn, originally run to finance the building of the church from beer sales. Given the theme of mutable female spiritual figures turned up by our wandering research method, it was incongruous but not surprising to find the pub sign comprised a woman on a white horse in a long blue robe, carrying a sword by the blade so its raised handle makes a cross, making her way through water and mist; by a church tower not dissimilar to the one across the road.

A little hive-mind research on Facebook turned up the signboard’s origin; an approximation of cover art for an Arthurian fantasy novel The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley; though the inn sign conflates Camelot with Torbryan by adapting its castle to look like the village church. The figure on horseback is the novel’s Morgaine, a version of the Lady of the Lake, who defends her ‘Celtic’ religion against the introduction of Christianity, eventually conceding defeat, but recognising that a trace of the old beliefs will continue within Christianity; her goddess assuming the mantle of the Virgin Mary.

After months exploring Torbryan and its surrounding small villages, the possibility we had been repeatedly led to consider as we tramped the narrow green lanes - that some faint trace of the Dumnonian goddess, the lady of the deep, had survived through The Old Grotto and in the official magical female figures in the churches - was played out on a pub sign.

All that said, in Bonelines this story plays out very differently.

The village of Torbryan in Devon includes a mediaeval church, a farm, The Old Churchhouse Inn, and a low cliff running about half a mile pitted with caves. One of these caves is named The Old Grotto by its original excavator, James Lyon Widger, and contains the remains of a medieval chapel. All these, according to drinkers at the Inn, are linked by a tunnel. (Aren’t they always?)

There is, surprisingly, no mention of this cave chapel in parish or diocesan records. This omission, and a suspiciously similar engineered rock fall blocking its entrance, led the archaeologist F. E. Zeuner to suggest that ‘The Old Grotto’ might be of similar nature to a contemporaneous chapel in the north of the county closed down by the church authorities for worshipping “proud and disobedient Eve and unchaste Diana”. Inside the cave are limestone formations that look like tentacles.

A chapel in a cave with submarine connotations (a river once ran through it) and a possible link to unofficial worship of unusual female figures dimly chimes with the local Iron Age worship of Dumna, a goddess of the deep. An earth monument of the Dumnonii people on top of nearby Denbury Hill is framed in the mouth of ‘The Old Grotto’ if you strand in the cave and look out.

Mediaeval rood screen paintings in the parish church in Torbryan include Catherine who was prone to mystical “ravishment” during which she went stiff as a board; Margaret who was swallowed by a dragon; Ursula, a Dumnonian princess who, inadvisably, led 11,000 unarmed handmaidens against an army of Huns; Barbara who opened a portal from a tower to a mountain and turned a recalcitrant shepherd to stone; Elizabeth who opened her robe to reveal a vision of roses, and Helena who found the true cross under a Temple of Venus.

Opposite the church is the Old Churchhouse Inn, originally run to finance the building of the church from beer sales. Given the theme of mutable female spiritual figures turned up by our wandering research method, it was incongruous but not surprising to find the pub sign comprised a woman on a white horse in a long blue robe, carrying a sword by the blade so its raised handle makes a cross, making her way through water and mist; by a church tower not dissimilar to the one across the road.

A little hive-mind research on Facebook turned up the signboard’s origin; an approximation of cover art for an Arthurian fantasy novel The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley; though the inn sign conflates Camelot with Torbryan by adapting its castle to look like the village church. The figure on horseback is the novel’s Morgaine, a version of the Lady of the Lake, who defends her ‘Celtic’ religion against the introduction of Christianity, eventually conceding defeat, but recognising that a trace of the old beliefs will continue within Christianity; her goddess assuming the mantle of the Virgin Mary.

After months exploring Torbryan and its surrounding small villages, the possibility we had been repeatedly led to consider as we tramped the narrow green lanes - that some faint trace of the Dumnonian goddess, the lady of the deep, had survived through The Old Grotto and in the official magical female figures in the churches - was played out on a pub sign.

All that said, in Bonelines this story plays out very differently.