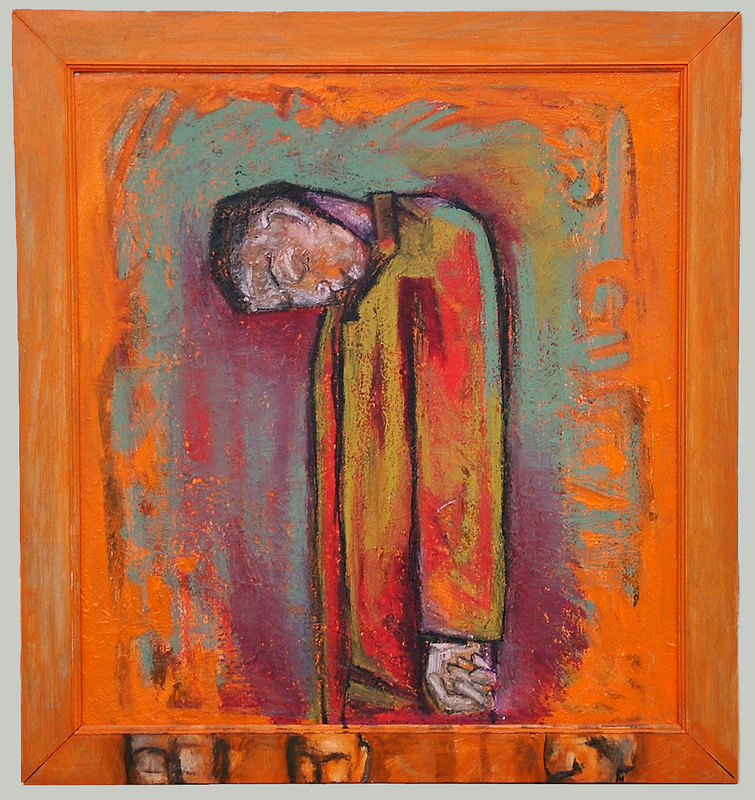

Exile

I draw my fingertips back towards my breast across this rough terrain, and think of how we carve our grief into each other’s face, being less the questors we thought we were and more like refugees, looking for a place. From Damian Ruth's poem Café Is exile a place or a status or a state of mind? Are exiles to be pitied or to be envied? What effect does the presence of an exile have upon those of us who are not exiles? Here are a few thoughts, taken from their context but provocative enough: "Where, when, does an exile begin? Shall I count the days since I left my mother’s womb? Shall I count each and every departure that left me freer, and her stifling tears? Shall I count my freedoms, and mark the distances that they entail? What restless calculations might I use to measure how far I am from home? Could such metrics assuage a yearning heart? Are we in exile when we cannot visit the graves of our fathers? Are we still in exile when we are haunted by the ghosts of our fathers?..." "Do exiles deserve special dispensation, a kind of pardoning, that leaves them alone to explore the liberation of space? To explore the anguish of dislocation, the struggle for new language? We do not pay enough attention to the struggle for language – language in the broadest possible sense... In one of Luis Bunuel’s films, Le Fantôme de la liberté, people scuttle off into little cubicles to eat their sandwiches in private, and then gather again to pee and defecate communally. How we apply the notions of public and private to an activity or condition can reveal much about it. Exile is like sex. It is a private activity, yet it is subject to communal mores. Exile is like eating. Eating is intensely personal; what could be more personal than what one ingests, takes into one’s own body? And yet we often and comfortably leave it to others to do almost everything to the food until the last final short journey into our mouths. And we are happy for that final journey to take place. Exile is a private anguish that can, through physiology, be forced into public. Exile strikes at the core of our being; we try to hide it, and yet so often we can barely contain it. We hide the pain, trying to avoid more, and thereby exile ourselves again, and our exile becomes a room of mirrors, repeatedly, endlessly reflecting our alienation. [All three extracts are from: Ruth, D. W. (2006). Exile: A moving wound. Auto/Biography, 14(3), 245-266. Sage Publications.] Credits and references: Luis Buñuel Damian Ruth |

Explore |