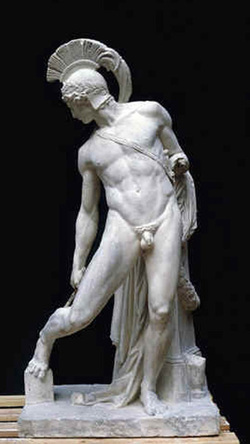

Achilles Syndrome

The following chapter from Inside Project Red Stripe - Andrew Carey's account of The Economist's innovation team - outlines Achilles Syndrome and has links to other resources: The late Petruska Clarkson - a Renaissance woman par excellence - is one of several people to have written about the Achilles Syndrome, or fear of failure worked up into a proper problem. Here are seven characteristics of the ‘Achilles Syndrome’, as described by her:

Some of these characteristics (including inappropriate anxiety when faced with having to speak in public) afflict most of us and I would classify them otherwise: as something to do with the desire to be special and to be seen as special, but the fear of being seen as ordinary. That may be another way of saying the same thing, though: Clarkson suggests that this syndrome has its origins in our upbringing and education, which tend to lay undue emphasis on success and performance in a competitive culture and which neglect basic human needs for love and respect in the quest for superiority. The result is what Clarkson calls ‘pseudocompetence’ – apparently advanced skills built on fragile foundations. I’m not interested in trying to diagnose whether the Project Red Stripe innovation team at The Economist suffered from Achilles Syndrome, though I suspect that, providing we accept the rather grand label of ‘syndrome’, probably most of us do. Connected to this, I began thinking about the twin towers of specialness and ordinariness when contemplating my shaking hands, flushed cheeks and growling stomach as I awaited my turn to ‘say my name and a little bit about me’ at a recent workshop. ‘This’, I thought, ‘really shouldn’t be such a big deal any more’. Then, in an interview in the Cambridge University Alumni magazine, the 12th Earl of Drogheda reveals that he didn’t join a dramatic society at university. ‘Now why would that be?’, the interviewer enquires. The conventional and anticipated reason (too shy) comes first: ‘I think this was because of a mixture of insecurity…’ The second, and rather unexpected, one comes next: ‘…and fear of not being given star roles.’ Hold it. Fear? Of not being given star roles? That looks like an unusual fear. Even in a world where we discover new phobias daily. But it echoes my conviction that much shyness and holding back reflects not our discomfort at being the objection of attention per se, but our grandiosity: our fear that we won’t be seen to be as clever, important, noteworthy, funny, beautiful as we think we really are – or could be. It reflects our unspoken expectation that we should be not just good, but significantly better than the others. So, we’re embarrassed to speak in public because we would like to be not just good enough but the finest orator in the land. And the Red Stripe collective clearly wanted a big success, even if they were nervous about saying this out loud. Tom, of course, wasn’t. At the outset, he said he wanted a massive success. So did Mike (the project team leader): ‘I want something fantastic’. And the team, in an early exercise where they considered what failure would look like, named ‘boring’, ‘incremental’ and ‘old business model’ as aspects of failure. Tom also made the connection with shame: if they failed there would be shame attached to that failure. Of course. Brave to say it, though. Tom’s naming of the word ‘shame’ is also a reminder of one downside of the very public profile that Project Red Stripe adopted. If the almost inevitable desire to aim high, to go for gold rather than settle for bronze, can become self-limiting when it means that teams exclude modest ideas that might lead eventually to revolution, then it can be all the more dangerous in the glare of publicity, where spectacular success is to be prized even more highly. The narcissism induced by publicity (and I use narcissism in its pseudotechnical sense rather than in its more common, pejorative sense) has been described by Cornell’s Professor Robert Millman as Acquired Situational Narcissism – a form of narcissism that develops in late adolescence or adulthood, and is brought on by wealth, fame and the other trappings of celebrity. So here, again, there’s perhaps a case to be made for a formal public face for the innovation team. The charm, flattery and seductiveness of the rhetoric of the goddess Peitha/Suadela needs to be carefully harnessed. Emmy van Deurzen also talks indirectly of narcissism when she discusses ‘living in tune with your intentions’. She cites the case of someone who wanted to be in control but tended to give up because she could never be fully in control. In Emmy’s view, she needed need to recognise the ‘limitations on being in charge, rather than a striving for absolutes.’ Striving for absolutes is the striving for specialness as against a recognition and acceptance of ordinariness. This recognition of limitations involves both a recognition of quantitative limitations (we can strive to be rich without striving to be the richest person in the world) and of the limitations of reality (in a fantasy world we may be able to fly, drink from the fountain of eternal youth or whatever, but in the real world we very probably can’t). In both cases, we can see the need for some tightening of the brief, some imposition of limitation on expectations, for the innovation team. Dilemmas If you hire people who know a lot about a particular subject, they may have a vested interest in showing that they know everything about it. Even if they don’t. Hiring people who know less may mean that you get people who aren’t embarrassed to admit the gaps in their knowledge and go out and fill them. Or it may just mean that you get people who know less.

Credits and references: Inside Project Red Stripe Michelle Smith on Specialness and Ordinariness Petruska Clarkson Emmy van Deurzen |

Explore |